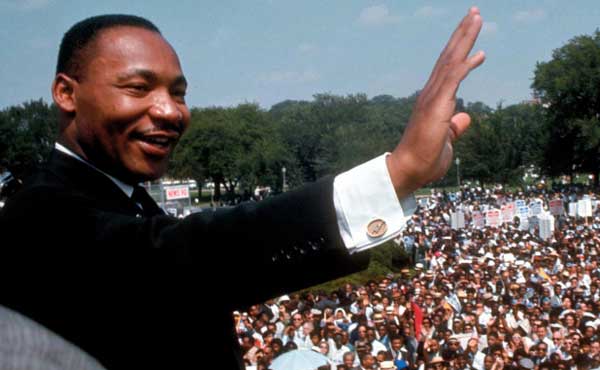

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Dream 50 Years After His Assassination |

KORVA COLEMAN, HOST:

Time now for The Call-In.

(SOUNDBITE OF CORDUROI'S "MY DEAR")

COLEMAN: Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn. His life has come to symbolize the struggle for freedom, equality and justice. We asked listeners if they see King's dream alive today.

ROBERT KOENIG: Hello. My name is Robert Koenig. I live in Bartlett, Tenn.

COLEMAN: That's right outside of Memphis. Robert Koenig believes that if King returned to the city now, he'd be deeply disappointed.

KOENIG: He'd find a troubled school system as segregated as it was on that day in 1968. He'd find thousands of African-Americans living in poverty and crime-infested ghettos. We are no closer to the mountaintop than we were on the day he died. And that's a shame.

COLEMAN: However, Maria Gil of Central Valley, N.Y., called in with a more hopeful take.

MARIA GIL: Prejudice and injustice still exist but so does the spirit of Martin Luther King. We saw it in the kids' marches that took place all over the world. And we'll keep seeing it.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PROTESTERS #1: Never again. Never again.

COLEMAN: From the student-led March for Our Lives rallies around the country to this weekend's Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Sacramento.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: What do we want?

UNIDENTIFIED PROTESTERS #2: Justice.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: What do we want?

UNIDENTIFIED PROTESTERS #2: Justice.

COLEMAN: Nonviolent protest was a powerful tool to bring about the dream Dr. King envisioned. But what really was his dream? To explore that, we called up Dr. Clayborne Carson of Stanford University, who edited and published Dr. King's papers. He says Dr. King had a deep commitment to social change, one that went beyond civil rights.

CLAYBORNE CARSON: People call him a civil rights leader. But he did that only because he happened to be living in Montgomery at the time when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat. I think his basic commitment was as a minister. He didn't retire after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in '65.

The next year, he was in Chicago trying to deal with some of the problems we still have today, the problems of the urban north. And I think for him, it was a wonderful victory to get civil rights legislation passed, but it simply made the South more like the rest of the nation. And the rest of the nation had a lot of serious problems.

COLEMAN: Fifty years ago, what was Dr. King's vision for America?

CARSON: Well, first of all, I think he saw things in global terms. He understood that issues like poverty, war, the lack of a sense of community - in one of his early papers, he says, you know, I want to deal with unemployment, slums, economic insecurity. And he didn't mean simply for black people. And that's what he was doing on the day he died. I think that was his true commitment.

COLEMAN: Do you think that vision's been realized today?

CARSON: Of course not. I think that he was probably less popular, certainly, than when he gave the I Have A Dream speech because he was confronting issues that we are still confronting today because they deal with the self-interest of many of us, you know? Many of us want social justice, but we don't want low-income housing in our neighborhood. So I think that it's always going to be more difficult to achieve changes that require major commitments of resources.

COLEMAN: Are there ways in which Dr. King's vision has been taken in a direction today with which he might disagree?

CARSON: I don't know if he would disagree with those people who are saying we should bring about change. He might disagree, sometimes, with the methods. He was strongly committed to nonviolent methods, but that doesn't mean he was against things that disrupted the peace. He understood that only when our normal routines are disrupted do we really pay attention to issues.

COLEMAN: And do you see generational differences in how people perceive Dr. King's work and legacy?

CARSON: I do. I think that for young people today, they weren't around when the civil rights bills were passed. So I think they have a purer notion of King. It's not - they see him as a symbol for social justice, a symbol for human rights. And that applies to their issues.

So I think that they see him as someone who would be supportive of Black Lives Matter and all the movements that are happening today because those are the issues that were left unfinished at the end of his life. I'm pretty sure from studying him for the last 30 years that he would be right out there with them.

COLEMAN: That's Dr. Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. So let's hear from a younger activist who's been inspired by Dr. King's legacy - Bree Newsome. In 2015, she drew national attention when she climbed the flagpole in front of the South Carolina Statehouse and took down the Confederate flag that was there. Bree Newsome, welcome.

BREE NEWSOME: Thank you for having me.

COLEMAN: We heard from Dr. Carson about the generational differences in the perception of Dr. King's legacy. What is your take?

NEWSOME: I would agree with his assessment. Young activists today really seem to focus on the latter part of King's life and when you look at King's last work - for instance, where do we go from here, community or chaos? - he's basically reflecting on what has been accomplished with the passage of the Civil Rights Acts but also acknowledging that, you know, the Watts riots came right after. So, clearly, simply passing the civil rights legislation while very important did not address deeper issues of poverty and of human rights.

COLEMAN: How was the role of class played into today's social activism? Can you talk about that?

NEWSOME: Yeah. I think classism has always been a factor in civil rights. But I think more recently, what we have seen is that middle-class black Americans have benefited from the gains of the civil rights movement, I think, in ways that the majority of black Americans have not. And things like mass incarceration, the war on drugs, welfare reform in the '90s, all of those things hit low-income black Americans much more harshly.

And so I think when we are looking at the modern civil rights movement or Black Lives Matter, you see those same kind of realities or tensions. Well, those who are most impacted most immediately by police brutality are those who are living in poor areas.

COLEMAN: You've written about this. In your activism around police violence, you actually have had to confront older civil rights advocates over tactics and what they think Dr. King would approve and your vision.

NEWSOME: Yes. And I think it's not even always necessarily about what King would have approved of but I think just in the moment, you know, making tactical decisions. The sit-in movements, for instance, of the '60s are celebrated now. But at the time, that was something that had never been seen before. And so it was a very radical act.

Similarly, the protest that you see young people engaging in today, blocking traffic, when you look back and you make that comparison, it makes sense that there would be some tension because I think those who lived through the time of Dr. King, they are aware of, you know, the reforms that came about or the progress that may have been made. But the fact of the matter is that this is still what we are experiencing as young black people in America. And we can't wait any longer.

COLEMAN: Do you think it's time for a new letter from a Birmingham jail encouraging people away from comfortableness and toward action?

NEWSOME: Yes. Absolutely. And I think this administration represents a very direct and blatant attack on civil rights in really trying to undo the civil rights movement. And so this is a moment very similar to the time and context in which Martin Luther King, Jr. was writing "Letter From A Birmingham Jail."

But here we are 50 years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. And I think part of what's happening right now is we are all asking, well, what constitutes progress, you know? If it's been 50 years and we're still discussing these same things, what does it mean to say we can only accept incremental progress?

COLEMAN: Bree Newsome is an artist, filmmaker and human rights activist. Bree, thank you very much.

NEWSOME: Thank you for having me.

(SOUNDBITE OF CORDUROI'S "MY DEAR")

COLEMAN: The Call-In is off next week. But if you have an idea for what you want to hear on the next one, let us know. Call us at 202-216-9217. That's 202-216-9217.

(SOUNDBITE OF CORDUROI'S "MY DEAR")

Copyright © 2018 NPR.