By the mid-1910s, the IWW had 150,000 members.

By the mid-1910s, the IWW had 150,000 members.

V.

John Dos Passos, one of America’s most widely read 20th-century writers, would later refer to Everest, a World War I vet, as a “sharpshooter,” alleging that he fought in the trenches of France. In his landmark novel 1919, Dos Passos claimed that Everest earned “a medal for a crack shot.” Elsewhere, Dos Passos made Everest sound like Daniel Boone, writing of the veteran, “His folks were of the old Tennessee and Kentucky stock of woodsmen and squirrel hunters.” Others have traded on the salacious tale that Everest married and fathered a child with Marie Equi, an Oregon lesbian, physician, and Wobbly icon.

None of this was true. Everest was a hard-luck case and a nobody who, by odd twists of fate, found himself at the center of a historic street battle on Armistice Day. He grew up on a farm in tiny Newberg, Oregon, and his life was shaped by trauma. His father, a schoolteacher and postmaster, died before Everest was even a teenager. In 1904, when he was 13, Everest’s mother was thrown from the seat of a horse buggy. Her head hit a rock and she died hours later, leaving behind seven orphans. “We children were distributed among aunts and other relatives,” his younger brother Charles wrote in a 1977 letter that offers one of the few original accounts of Everest’s life.

For Everest, the third-oldest child, the fatal accident gave way to an unsettled existence. At first he lived on a great-aunt’s farm outside Portland, and then, when milking cows no longer agreed with him, he ran away. He wasn’t yet 15. “I do not know where he went or what he did,” Charles wrote, “but I heard he was felling timber in the woods at age 17.” Charles didn’t see his brother again until 1911, when Everest got a job on the railroad near where Charles lived. “He worked a short time,” Charles wrote, “and disappeared.”

Everest was working for the IWW by the age of 21. In 1913, he was on Oregon’s southern coast, in the village of Marshfield, organizing a logging strike summed up eloquently in a headline that appeared in The Coos Bay Harbor: “35 Men Refuse to Work in Deep Mud. Strike for Less Hours and More Pay.” The six-week campaign failed. Along with another Wobbly leader, Everest was escorted out of town by what The Coos Bay Times called a “committee” of 600 armed citizens—a group that included “practically every businessman in Marshfield.” The men dragged Everest through the streets until he was scarcely able to walk. They forced him to kneel and kiss the American flag. They put him on a boat bound for a distant beach. And they advised him to never return to Marshfield, “as he might,” in the newspaper’s words, “suffer greater violence.”

When Everest was conscripted in 1917, it was into a special contingent of the Army that logged spruce for airplanes in western Washington. He stubbornly resisted the lessons of Marshfield. During his 16-month Army hitch, he spent much of his time in the stockade, repeatedly punished for refusing to salute the American flag. “In the mornings,” writes John McClelland Jr., the author of Wobbly War: The Centralia Story, “Everest would be let out of the stockade at reveille when the flag was raised. Everest would refuse to salute whereupon he would be marched back to the stockade for another day.”

Everest arrived in Centralia in the spring of 1919, and he liked to wear his Army uniform around town. It allowed him to blend in, and he likely donned it on a visit to the Elks’ clubhouse, where a group of concerned Centralia citizens gathered that October to discuss the threat of organized labor. He came away convinced that the town’s citizens were determined to shoot up the IWW hall on Armistice Day. “When those fellows come,” he told other Wobblies at their own meeting, “they will come prepared to clean us out, and this building will be honeycombed with bullets inside of ten minutes.”

It was Everest who argued that the Wobblies should arm themselves for the parade. Listening to him make his case, 21-year-old IWW logger Loren Roberts concluded that Everest was “a desperate character. He didn’t give a goddamn for nothing. He didn’t give a damn whether he got killed or not.”

Everest had been right that the Legionnaires were planning an attack. He was wrong, though, about the hall being “honeycombed with bullets.” When Grimm’s men charged, they were unarmed.

VI.

As the Legionnaires forced their way inside the hall, Everest and Ray Becker, the minister’s son, shot wildly, hitting no one. The vets kept coming. Four Wobblies, including Becker, ran to the back porch of the Roderick, where they hid in an unused freezer. Everest kept running, past the porch and into an alley. Men in military uniform sprinted after him. He kept shooting, and this time his aim was good. Ben Casagranda, a Legionnaire and the owner of a Centralia shoeshine parlor, fell to the ground with a bullet in his gut. Another veteran, John Watt, fell beside him, hit in the spleen. Watt would survive; Casagranda would not.

The Legionnaires, who greatly outnumbered the Wobblies, began asking neighbors of the Roderick for their weapons. Some broke into a hardware store, searching for guns and cartridges. A few who were still unarmed followed Everest at a careful distance.

Everest scrambled west down alleyways, through vacant lots, and past horse stables. He was moving toward the Skookumchuck River, less than half a mile from the IWW hall. On the north bank were farms and forests through which he could escape into the mist.

As he ran, Everest stopped every so often to hide behind a building and shoot at the soldiers on his trail. He missed, wasting bullets. When he got to the river, it was swollen with autumn rains and moving too quickly to cross. Everest was trapped.

F.B. Hubbard’s nephew, Dale, lumbered toward him, pointing a pistol at Everest as two other Legionnaires hurried to assist. He instructed Everest to drop his gun. Like Grimm, Dale Hubbard had played football at the University of Washington. He’d served in France, with a division of forestry engineers, and gotten married a month earlier. He was 26. He’d borrowed the pistol he was holding from someone he’d encountered en route to the riverbank. The gun didn’t work, though—Dale was bluffing.

Everest didn’t know this, and he likely regarded Dale’s steady pointing of the weapon as a death threat. Still, he didn’t acquiesce to the command that he drop his pistol. Instead, according to legal papers, Everest hurled “defiant curses” at Dale. When Dale moved toward him, Everest fired repeatedly, wounding Dale repeatedly. Dale fell to the ground. He would die that night.

Everest had just shot a veteran in front of two other soldiers, and his gun was now out of bullets. He tried to reload, but Dale Hubbard’s allies tackled him. The Legionnaires kicked him in the head, drawing blood. When he refused to walk, they strung a belt around his neck and dragged him a mile to the Centralia jail.

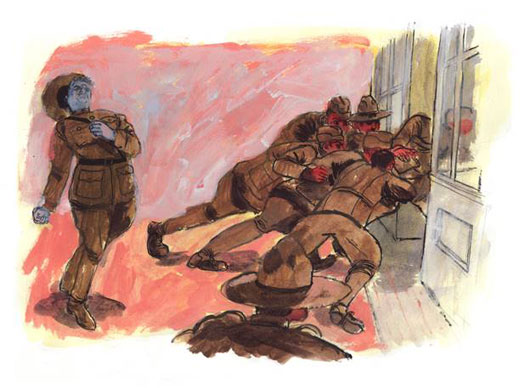

The assault on the IWW hall.

The assault on the IWW hall.

VII.

As Everest was hauled through town, no one asked questions. Instead, a crowd grew around him, convinced he was evil, and eventually he found himself “in the vanguard of a howling, sneering mob,” one witness wrote decades later in the Chronicle. “His head was a bloody mass of welts from both men and women who dashed out sporadically from the curb to pummel him with their fists.”

Someone in the mob threw a hangman’s noose around a light pole, according to one eyewitness. Everest was led beneath it. As he stood waiting for his end, he berated the crowd, calling them “cowards, rats, and Hubbard’s hirelings.” As the crowd aggravated for the Wobbly’s demise, an elderly woman intervened and begged Everest’s tormenters not to hang him.

Soldiers lifted Everest off the ground by his neck and feet like a sack of potatoes. They tossed him into a jail cell. As he lay in a pool of blood, squads of Legionnaires combed the streets of Centralia looking for other Wobblies. The IWW hall had been ransacked and destroyed. Mobs burned the Wobblies’ furniture in the street, along with piles of books and labor newspapers. They tore a porch off the side of the Roderick, prompting the building’s worried owner, Mary McAllister, to hastily install an American flag in her window lest the whole place be leveled.

Across the street, O.C. Bland wrapped a towel around his bloody hand. He left the Arnold Hotel, crossed Tower Avenue, and walked east, hoping to convalesce at a friend’s. When he reached Seminary Ridge, he encountered Davis, the crack Wobbly gunman who had likely killed two people that day. The Legionnaires were searching for him. When The New York Times reported on the hunt the following morning, it wrote that the servicemen “searched the highways and byways for all suspicious persons and then sent out parties into the timbered country around the city.”

When they could not find Davis in the open air, the Legionnaires stormed a seedy, smoky pool hall. According to the Times, they “lined about 100 persons against the wall and searched them.” Sixteen men carrying IWW cards were arrested. At least 25 alleged Wobblies ended up in Centralia’s jail alongside Everest.

At 5 p.m., Centralia’s Elks and Legion Post #17 gathered for an emergency meeting in the Union Loan & Trust Building. They adjourned briefly to return home for their guns, then convened again to devise a plan of action, booting anyone who was neither an Elk nor a Legionnaire from the room.

Shortly after the men emerged at 7 p.m., they arrived at the jail in a caravan of six vehicles, each of which had its headlights switched off. The men occupying the vehicles had no problem getting inside. The jail was guarded by a lone watchman, and they were operating under cover of darkness—someone, possibly Centralia’s mayor, had managed to temporarily cut the electricity flowing from the town’s power plant.

“The first person to enter the jail was F.B. Hubbard,” Esther Barnett Goffinet, daughter of Wobbly Eugene Barnett, wrote in her 2010 book, Ripples of a Lie. “Someone in front of the jail turned their headlights on and Hubbard yelled, ‘Turn off that light! Some IWW son-of-a-bitch might see our faces.’”

It’s not clear that Hubbard actually said this—or that he was even at the jail that night. Goffinet’s source was a pair of affidavits given several years later by two Wobbly prisoners with an ax to grind. Still, the vignette gets the deeper story right. Working his connections and exercising his clout, Hubbard had spent much of 1919 quarterbacking Centralia’s war against the red scourge. Now his ugly hopes were coming to fruition.

The posse dragged Everest outside, where a crowd of about 2,000 people were now “swarming like bees,” the Tacoma News-Tribune reported. “They were rough men, angry, scornful men whose pockets bulged menacingly with the weapons they made small effort to conceal.” Some in the crowd wanted every single Wobbly in Centralia to hang. They shouted, “Lynch ’em!”

The caravan moved west, bound for the broad Chehalis River. Everest was defiant. “I got my man and done my duty,” he said, not specifying which of his victims he intended to kill. “String me up now if you want to.”

Men who were never charged in court knotted a noose to a crossarm of a bridge over the Chehalis. They put it around Everest’s neck and let him drop. A moment later they heard a low moan and knew that Everest was still alive—they’d flubbed the hanging. They pulled him up. They found a longer rope and let Everest drop again. This time his neck snapped. When at last his body went limp, the vigilantes in the caravan turned their headlights on so they could take aim. They shot some 20 or 30 bullets into Everest’s corpse.

They left his body dangling. Early the next morning, November 12, someone cut the rope. That evening, the Seattle Star reported, Everest’s corpse “was dragged through the streets. The body was taken to the jail and placed in a cell in full view of 30 alleged IWW prisoners.”

“The sight was intended as an object lesson not only for the prisoners huddled in their cells,” the Star noted, “but to all men who fail to respect the men who fought for the United States.”

VIII.

In the lyrics to a 1920 song titled “Wesley Everest,” Wobbly Ralph Chaplin channeled Christ’s crucifixion as he envisioned the activist hanging from a noose. “Torn and defiant as a wind-lashed reed,” the song goes, “a rebel unto Caesar—then as now—alone, thorn crowned, a spear wound in His side.” In The Centralia Conspiracy, a book published the same year, Chaplin burnished Everest’s martyr status by suggesting that his killers had castrated him. “In the automobile, on the way to the lynching,” Chaplin writes, “he was unsexed by a human fiend, a well known Centralia business man.”

The story of Everest’s castration is arguably the most remembered detail of the Centralia tragedy. It is so widely accepted that Howard Zinn presented it as fact in A People’s History of the United States. The story is likely bogus, however. In a meticulous 1986 essay, Wesley Everest, IWW Martyr, author Thomas Copeland makes clear that, in late 1919, not a single report—from journalists, from Everest’s fellow Wobblies, or from the coroner—mentioned castration.

Still, Chaplin’s mythmaking is nothing compared with the stagecraft of the trial that ensued after the Armistice Day violence. In early 1920, in a courthouse in Montesano, Washington, 11 Wobblies stood accused of committing murder during the shootout. To intimidate the jury, Hubbard’s company joined other citizens in paying 50 World War I veterans $4 a day to sit in the gallery dressed in uniform. Outside the courtroom, the soldiers enjoyed free meals at Montesano’s city hall and met trains to discourage IWW supporters from disembarking.

The judge presiding over the case, John M. Wilson, refused to let the jury consider the buildup to the shootout—the 1918 attack on Centralia’s IWW hall, for instance, and the October meeting at the Elks Club to discuss the “Wobbly problem.” Prosecutor Herman Allen, meanwhile, turned the proceedings into a circus. Mid-trial, Allen summoned assistance from the Army as what he called a “precautionary measure” against Wobbly violence. Eighty enlisted men were dutifully sent to town. The troops, who arrived armed, camped outside the courthouse for two weeks and stirred such fear that two jurors secretly carried guns in case of a Wobbly attack. Their fear was unfounded, however. Nobody on the union’s side was calling for an uprising in Montesano. In fact, leftist protestors stayed away from the heavily patrolled town.

For the Wobblies on trial, there was one sliver of light: Davis, the stranger who’d probably killed two Legionnaires, had escaped. Somehow, despite extensive searching, Davis had vanished, never to be found. The only other Wobbly known to have killed anyone was Everest, and he had been lynched. As it sought payback for the death of four Legionnaires—Grimm, Hubbard, Casagranda, and McElfresh—the prosecution offered a tenuous argument that the defendants were to blame.

Allen tried to build a case that Wobbly Eugene Barnett, not Davis, had leaned out the window of the Avalon Hotel to kill Grimm. Credible testimony, however, suggested that Barnett wasn’t even in the Avalon when the shooting broke out; he managed to wriggle free of first-degree-murder charges. In the end, the jury zeroed in on the planning that had gone into the Wobblies’ armed resistance, and found seven men, including Barnett, Ray Becker, O.C. Bland, and Britt Smith, guilty of second-degree murder. Each received a 25-to-40-year sentence.

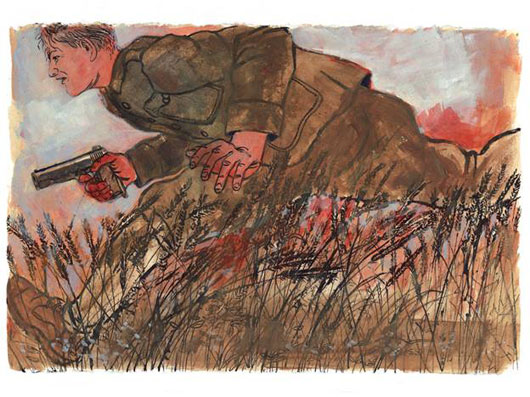

Wesley Everest

Wesley Everest

IX.

Wesley Everest, Warren Grimm, F.B. Hubbard—indeed, everyone who walked the streets of Centralia in 1919—were bit players in a larger drama. Throughout American history, corrupt power had always found a way to justify cruelty by reframing truth and instilling fear. In 1830, when Andrew Jackson forced thousands of Native Americans west along what became known as the Trail of Tears, he asked, “What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms?” In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court enshrined white supremacy under the false promise of separate but equal.

In the case of Centralia, the shootout shook an already anxious nation. Three days after it happened, The New York Times ran an editorial declaring that the incident “has probably done more than anything else to arouse the American people to the existence, not of a menace to their Government, but of human miscreants from whom no life is safe, however humble.” The Red Scare would die out in 1920, when the Justice Department lost face by issuing warnings about a May Day anarchist uprising that never happened. Still, Centralia left its imprint. A new suspicion had wormed its way into the back of the American mind. Citizens opposed to leftist politics now harbored a heightened sense that evil could emerge anywhere, even in the streets of a small town in the woods.

Centralia also afforded young J. Edgar Hoover an opening. At the time, Hoover was still living with his parents, but in the wake of the Armistice Day tragedy, the world opted to take him seriously. He ran with it. In a memo, he asked an aide to “obtain for me all the facts surrounding the Centralia matter.” The following month, four days before Christmas, at 4 a.m. in the frigid darkness, Hoover showed up at Ellis Island. The 249 Russian dissidents he had rounded up were herded toward a creaky old troopship that would carry them back to the Soviet Union. Soon, Hoover began compiling a file on Isaac Schorr, the activist lawyer who represented many Ellis Island detainees. Then, on January 2, 1920, Hoover orchestrated his biggest set of raids yet. This time, at least 3,000 suspected communists were captured in more than 30 U.S. cities—all on the same evening.

In time, Hoover became the most prominent reactionary public official in America. Instrumental in the FBI’s founding, he directed the agency for 48 years and kept secret files on thousands of Americans. When a reporter once asked him whether justice might play a role in addressing the civil rights movement, Hoover responded coolly, voicing words that might have played well in Centralia in 1919 (and the nation’s capital today). “Justice,” he said, “is merely incidental to law and order.”

Throughout the 1920s, a dedicated and conscientious Centralia lawyer, Elmer Smith, tried to fight Hoover’s law-and-order approach. He led a campaign to free the Wobblies convicted of conspiring to murder Legionnaires on the first Armistice Day, and he did so with such flourish that he once drew 5,000 people to a speech in Seattle. That day, Smith argued that the Northwest’s lumber barons, having sent the Centralia Wobblies to jail, also had the power to free them.

Smith got no judicial traction, though. The Wobblies languished in prison. One of them, an Irishman named James McInerney, died of tuberculosis in 1930 while behind bars. The following year, Eugene Barnett was allowed to go home to nurse his wife, who was sick with cancer. O.C. Bland was paroled soon after, and in 1933, Washington’s then governor, Clarence Martin, granted parole to three more Wobblies.

Only Ray Becker, the minister’s son, remained behind bars. Bitter, paranoid, and holding firm to his anti-capitalist convictions, Becker refused to seek parole. Instead, he wrote handwritten pleas—to newspapers and also to a judge—as he sought admissions of guilt from everyone he believed had conspired in framing him for murder. Becker did not leave jail until 1939, when Governor Martin announced that, after 18 years, he had served his time.

X.

The legacy of the Centralia shootout is still palpable in the town. In the center of its main green space, George Washington Park, fronted by a long, regal concrete walkway, is a bronze statue erected in 1924. The Sentinel features a helmeted World War I soldier, his lowered hands gently wrapped around the barrel of a rifle. An American flag flutters high on a pole behind him, and an inscription on the statue’s side honors Warren Grimm and the three other soldiers “slain on the streets of Centralia … while on peaceful parade wearing the uniform of the country they loyally and faithfully served.”

Not 200 feet from The Sentinel’s patinated nose, on the exterior wall of the Centralia Square Hotel, is a bright mural titled The Resurrection of Wesley Everest. Awash in splashy oranges and yellows, installed by artist Mike Alewitz in 1997, the mural depicts the lynched Wobbly with his arms held high in victory. Flames crackle beneath him; they signal, Alewitz has said, “discontent.”

When I visited Centralia not long ago, I stayed at the Square Hotel, so that every time I stepped into the street I found myself crossing the energetic force field between the statue and the mural. It was pouring rain most of the time I was in town, so usually I hurried, intent on staying dry and on ducking the bad municipal feng shui achieved by the memorials’ counterposition.

Once, though, heading out for an interview near the former home of the IWW, I paused in the space between. I watched as the flag above The Sentinel was pelted by steady rain. The shootout in Centralia was a fight over what that flag meant. One side wanted an America that was fair and equitable, framed by the right to free speech and steeped in justice for all. The other was mesmerized by the battlefield glory that the flag represented, the legacy of bloodshed knitted into its stars and stripes. In their opinion, such a legacy demanded obedience. It was worthy of vigilant defense, and if marginal citizens did not behave like 100 percent Americans, well, it didn’t matter if they got trampled.

Standing there, I wanted to believe that in the 101 years since the Centralia shootout, the Legionnaires’ cruel patriotism had withered away—that the intervening century had delivered the nation to a gentler, more humane outlook. But I knew that wasn’t completely true. In recent years, Donald Trump had resurrected the exclusionary nationalism of the early 20th century, justifying racist and xenophobic policies under the banner of making America “great” again. At the same time, a socialist was a legitimate contender for president—twice—and Black Lives Matter grew into the largest social justice movement in U.S. history. There was still hope, but it had to be nourished.

The rain picked up. I was running late. I hurried north toward the scene of battle.