The Tattooist of Auschwitz, and the love that helped him survive |

AMT: Hello. I'm Anna Maria Tremonti and you're listening to The Current.

SOUNDCLIP

[violin plays]

VOICE 1: Could you tell me your name please?

VOICE 2: My name is Lu Sokolov. I was born near Eisenberg.

VOICE 1: What name are you known as?

VOICE 2: Lale. They called me Lale.

VOICE 1: What was the name of your wife?

VOICE 2: Gita Sokolov.

VOICE 1: Where did you and Gita meet?

VOICE 2: In Auschwitz-Birkenau.

VOICE 1: And how did you meet?

VOICE 2: I was the tattooist in Auschwitz-Birkenau. I tattooed her number on her left hand and she tattooed her number in my heart.

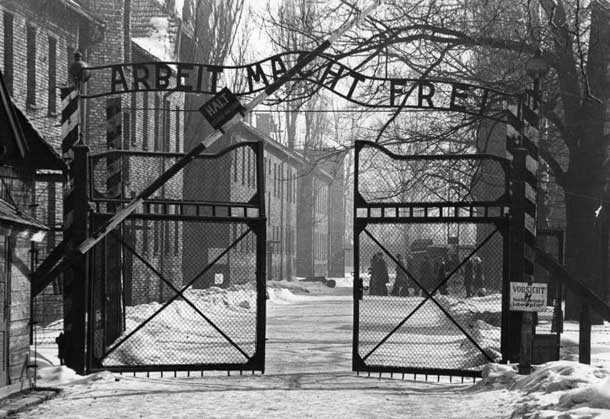

AMT: You just heard Holocaust survivor Lale Sokolov speaking to author Heather Morris, 60 years after his escape from the concentration camp, where he saw so many of his fellow Jews die. For many years he was assigned the job of tattooist of Auschwitz, inscribing numbers on the arms of prisoners as they entered the camp. It was a story he kept mostly to himself for decades, afraid of being seen as a collaborator because of the privileges that position gave him. After the death of his wife Gita, whom he met in Auschwitz, Lale Sokolov shared his memories with Heather Morris. They spoke several times a month, over many years, at his home in Melbourne, Australia. Lale Sokolov died in 2006. Heather Morris has turned the story into a novel. It's called, "The Tattooist of Auschwitz" and she joins us from Melbourne, Australia. Hello.

HEATHER MORRIS: Hello.

AMT: It's so interesting to hear his voice and so much to ask you about. First of all, how did he come to be the tattooist at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps?

HM: He was destined to die within weeks of being transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He got typhoid and he was thrown on the death cart. One of the prisoners that he shared a block with was taking him off because he knew he wasn't dead and a stranger came along and helped him. And for seven or eight days the men in the block and that stranger, another prisoner, cared for him. And when he was well enough, that stranger took him outside and introduced himself. He said I am Pépan I am the tatowierer, I would like you to come and work with me. And so he got the role being the assistant. He was only the assistant for a few weeks and one day he went to work and Pepan wasn't there and he was told by the camp commandant you are now the tatowierer.

AMT: And it was really by their whims. The original man was likely taken away and killed.

HM: Yes. We could not find him. We've had researchers searching for him, but we didn't have his surname cause Lale couldn't remember it. So we can only presume he was killed immediately.

AMT: Now he came from Slovakia. How what happened to him to get him to Auschwitz?

HM: Well Slovakia was the first country really that started handing over young Jewish boys and girls, men and women, to go and work for the Germans. And he volunteered when the Germans issued an edict. Every Jewish family had to surrender one child over the age of 16 to go and work for them. Now Lale had an older brother who was married with two small children and he had a sister and there was no question that he would go.

AMT: He was tattooing the people who were coming in a very infamous of course, numbers on their four arms. How did he describe the process of tattooing?

HM: He rationalized it to himself and he needed to do that, by saying that if they came to him, that meant that they would see the sun come up the next day and maybe the next day after that and the week after that. He knew that everybody who didn't come to get tattooed, they didn't get to see the sun come up the next day.

AMT: He couldn't have refused at that point, could he have?

HM: Oh no not at all. He wouldn't have seen the sun come up the next day.

AMT: Lotte Weiss was one of the people whose arm he tattooed and she now lives in Sydney, Australia. Let's listen to what she remembers about Lale.

SOUNDCLIP

VOICE: He did my tatoo. I can't forget it. C2063. He was a very good chap you know. I knew that he did on all the girls, so there was no sense in being angry with him or anything. Nothing. He was a good friend and then he married Gita and Gita was a good friend of mine, before and in Auschwitz. Very often I think God looked after me because my sister Celilia and Erica, they died two days within each other and they had similar number to me. But I tell you something, it was so horrible for us when we were there, the suffering. I was so bloody lucky. My luck was Lale and gita and if you needed each other, you know we were there, one for the other and it was just sheer luck.

AMT: Heather Morris, we get a little sense from that and you know over time, we have learned about the horrors of the Holocaust, but she speaks there about the bond amongst those people who would do, would help each other. And you spend a lot of this novel kind of looking at that. Yes that friendship, that bond, you know in a funny kind of way, Birkenau was a community. People had jobs, some had privileged jobs like Lale. People looked out for each other. And it was the humanity that Lale saw time and time again of one person doing something small, sharing their bread, helping in any small way they could. That's what kept them all going.

AMT: Lotte also remembers that Lale marries Gita and we heard Lale say earlier that she tattooed her number on his heart after he had tattooed a number on her arm. So he knew the number. How did he find out her name? It was a big place. He actually, like he was looking for after wasn't he?

HM: Absolutely. He had a minder, an SS minder, who he described to me as being an uneducated oaf, somebody that he learned when to walk in front of, when to walk beside and when to walk behind him. He learned how to manipulate this man and he got from him, Gita's name. He gave Baretzki the number and he said would you find out who she is and where she is? And Baretzki did it for him. They have a relationship, which yes can be called into question, but please, understand at all times, Lale was just using and manipulating this person.

AMT: And we'll talk a little bit more about that after, but in terms of Lale and Gita they fall in love. How do they fall in love in such a terrible place?

HM: Well Lale fell in love first. He was the one who was totally smitten. When he held the arm of her, an 18-year-old girl dressed in rags and her head shaven, he knew that in that second that he could never love another. And you have to understand that this man had been something of a playboy before he went in to Birkenau. Now Gita, she wasn't the same. She saw no reason to get to know him initially. To her, they were never going to leave that place other than through the chimney. He just had to have the faith for the two of them.

AMT: She wouldn't give him her last name. Why not?

HM: No. Because there was no point in it. She couldn't see them ever leaving there and so she played it really tight in terms of how much information she would share about herself and he accepted that. He knew sooner or later they were going to leave there. He just wouldn't have it any other way. Yes, he also described the fact that he survived as being just lucky, lucky, lucky, but also he helped manufacture that luck by being an opportunist and looking out for others.

AMT: So they looked at their circumstances differently. She thought they weren't going to get out and he had this hope and it's almost as if by by falling in love with her, he had a reason to hope for a life after that.

HM: Absolutely. There were many occasions, he walked alone between the two camps. There's four kilometers between Auschwitz and Birkenau. When Baretzki was either too hung over or couldn't be bothered making the journey, he let him walk alone, unescorted, because he knew he would not run away. There was no way Lale would be leaving that camp without Gita.

AMT: What privileges did he get from his job as the tattooist?

HM: Well the most significant privilege was freedom of movement. Because he could be in any part of the camp, it also meant that he could get access to the girls who were going through the belongings of the prisoners and get from them, money and jewels that they smuggled out. And with that, run his black market, where he could help as many people as he could.

AMT: He would get diamonds and rubies and gold, what would he do with it?

HM: Well he befriended some of the villagers. You know that was one of the things that struck me the most. I did not comprehend that people who worked and lived nearby, came into Auschwitz-Birkenau every day and carried out a 9 to 5 job and then went home again. I talked about that with Lale because I just couldn't comprehend that knowing what they were doing there and he was quite sort of matter of fact about and he said, oh they had families to feed. But it was those villages that he was able to give them money, the jewels, the diamonds, and they in return brought him food in particular.

AMT: And what would he do with the food?

HM: Distribute it as far and wide as he could. Break it into small pieces.

AMT: Those local workers were coming in to build more areas for the new prisoners to sleep and of course more gas chambers and more crematoria.

HM: Exactly.

AMT: So he was doing this, this is very dangerous, as you mentioned, he has an SS guard assigned to him named Stefan Baretzki. And you make the point that he's able to manipulate him. Tell us more about that relationship.

HM: He wasn't that much younger than Lale, but he was an uneducated man, who was spellbound by Lale in some ways. That's how I worked out their relationship. He saw in Lale somebody that he probably would like to be and so he thought he could learn from Lale. Now Lale was happy to tell him anything he wanted to hear.

AMT: But he always ran the risk that Baretzki could have just shot him in the head.

HM: Yes he could have. Now, yes and no in some ways because the reality was that Lale was doing a good job. And if Baretzki had decided to take out the camp tatowierer, he might have had to answer to one or two other people.

AMT: He says many times through the character Lale in the novel, that he would do what he needed to do to survive.

HM: Pretty much, yeah. I suspect that there would be a line in the sand he would have drawn, if he had to, but I don't think he got tested to the limit of doing anything that morally, he could not live with himself.

AMT: And he often encountered the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor, when he was tattooing new arrivals. What did he tell you about Mengele?

HM: Nobody in Auschwitz-Birkenau put the fear of God in him, quite like Mengele did. He gave him the shudders. He couldn't look at him. Mengele threatened him whenever he could. He was, he said, pure evil.

AMT: And Mengele was essentially, sort of he would show up around the people coming in to be tattooed because he just, he was literally choosing who to experiment on.

HM: The selection. That's what the process was called. And they would either be selecting them to just either live or die or if he decided to turn up, he would be selecting them to be his guinea pigs.

AMT: He does tell you the stories of people that, in fact, his own assistant is at one point chosen by Mengele.

HM: Leon, yes. And he thought that that was in some kind of retaliation for Lale. Having a bit of bravado around him once, yeah he couldn't take Lale. The commandant of the selections wouldn't let him. So he took his assistant, Leon, instead.

AMT: Can you tell us what he did to him?

HM: He castrated him. He didn't kill him and he came back, but he castrated him.

AMT: So horrific. Lale gets out of Auschwitz and ends up back in Slovakia. What time frame are we talking here?

HM: He in fact left Auschwitz on a train for another camp on the 27th of January, 1945. We mentioned only a few hours before the Russians arrived and liberated the camp. He was given the choice to stay or to guard and he feared that it would just be open slaughter for all those that remained and so he did get on that train and go to another camp and from there he got transferred to another camp, as well. That was just outside of Vienna. It was from there he escaped. He just decided one day, enough was enough. And it was the camp that was run by mostly elderly German soldiers and they didn't care. Things were not going well for them. They knew that. And he just stuck his way out underneath the fence and found himself opposite the Danube River. He knew that the Germans were on one side and the Russians were on the other and he needed to get to the side the Russians were on and then after trying to swim to get to the other side and he couldn't against the current. He said he just had to float like a log and play dead.

AMT: He makes it back to Slovakia, but he ends up on the Russian side and is put to work for them.

HM: Yeah with the Russian hierarchy, in a castle full of fine art and tapestries and the Russian hierarchy made it their headquarters and yes they worked out that he spoke both German and Russian because he did. He spoke five languages and they put him to work. He said I was a pimp. I have to hang my head in shame. I was a pimp. He would go each day to the village and he would arrange for young girls there to come in the evening to be the, yeah the female companions to the Soviet or the Russian hierarchy that were there. He said it was mostly the men, they would get drunk, girls would eat and drink and then they'd get driven back home again. They were happy to come. They got a meal, they got good food, they got good wine. He paid them in jewels because he was given jewels to buy them with.

AMT: That the Russians had confiscated, obviously.

HM: Absolutely.

AMT: From some of the places they took right. And how did Gita escape?

HM: Gita was taken on a death march and he watched her go. She marched for about two days, through the snow, through the forest. This is January. They got to a point where she and three other young girls from Poland made the decision, we can keep marching and as we fall, we'll be shot or we can run. And yes, they saw a house through a forest and it took her six weeks of hiding in the forests and in villages, being hidden before she managed to make her way back to Slovakia and got back to Bratislava.

AMT: And he has a last name, that's about all he's got. How did they find each other again?

HM: Lale went looking for Gita at the train station. Every day trains were coming in from Europe with displaced people and prisoners returning and every female he saw, he would ask them, were you in Birkenau? Were you in Auschwitz? Did you know Gita? Of course he didn't find her initially and he was told, get back into town. There's a Red Cross has set up a building there and register your name. Now he had a horse and a little cart, just big enough for one person to stand on the back. And he was driving or riding down the main street of Bratislava, heading for the Red Cross building. She was walking towards him with two of her girlfriends. She saw him and she found him and she stepped out in front of the horse and I know it's a Hollywood ending and I have to feel like I should apologize for that, but it's how it happened. And he literally did just drop to his knees and say marry me.

AMT: So they end up in Australia, which is where you meet him. How do you come to be the one who hears his story? Who he chooses to tell this to.

HM: Like Lale I was lucky, lucky, lucky. I was having a cup of coffee with a friend and she casually said to me, oh I have a friend whose mother's just died and his father has asked him to find someone he can tell a story to and that person can't be Jewish. Now she was Jewish, she knew I wasn't. And she said would you like to meet him? And I said yes. And a week later I knocked on the door to his apartment and I meet him.

AMT: Why did you have to not be Jewish?

HM: That was very, very important to him. He wanted to talk to somebody who had no history, no baggage, no family connection to the Holocaust that could in any colour how I would interpret and write what he wanted to tell. He actually quizzed me at length about what did I know about the Holocaust and I was ashamed to have to admit that my small town, New Zealand education, really hadn't given me much. And so to him that made me perfect.

AMT: And why was that. What was he afraid of?

HM: That a lot of people, who I've met who are survivors that all got different stories. They all have a different interpretation on what was right and what was wrong. I guess to him having somebody who clearly would have none of that baggage made for the perfect person.

AMT: Was he afraid of being judged as a collaborator?

HM: Not by his community here, but he did fear that if his story became widely known that somewhere out there, somebody may point their finger. And he was also, the fact that Gita never spoke about her time there. Not to their son, only ever to Lale himself. So he could not talk about it, while she was alive because she didn't want him to and he respected that and that fear that somebody might consider him to be a collaborator. And I've spoken to many, many people now in many countries. Spoken at synagogues from London to Sydney and beyond and nobody's even hinted he should have thought that way.

AMT: And yet we do know that in your book you talk about how he was an assistant to the capo for a short time. Tell us what a capo is.

HM: A capo or blockleiter was a person who got to have that single room at the front of every block and their role was just to make sure the rest of the persons on the block went to work. They didn't have to work. Look there were good ones and bad ones and I've read many testimonies of people who had some pretty harsh things to say about capos.

AMT: That's why I brought it up because there are those people who use that as a shorthand to attack others you know in terms of like making a Nazi reference and he would have been sensitive to all of that, right.

HM: Oh absolutely.

AMT: I mean it's so complicated, but it offers a glimpse into people in great trauma and misery and captivity and what some do to try to just breathe the next day. It takes another look at it right, it's not superficial to look at how people end up doing what for their captors.

HM: No. And I guess sometimes the lines were crossed and they were the ones who would yell and scream and make out in front of the SS, that they were the tough capo that was going to keep their block in line, but there were also some that took delight, what seemed, took delight in actually hurting, injuring making prisoners suffer.

AMT: You told Lale's story, but you chose to tell it as a novel, as opposed to a straight up account chronicling what he went through. Why is that?

HM: Strictly, if I was to write it as a memoir or biography, I could not have Gita and the other players in there. I could not write dialogue. I could not weave this beautiful love story into all those facts that we know were going on in that camp at the time. And I had admit, there were two occasions I put Lale and Gita together, that they weren't, for dramatic effect. And so as soon as I did that, as soon as I wanted to have a presence with Gita, have her story of what was going on in the block with her and the girls. It was no longer a memoir. I'm really proud of the fact that I chose that format because it enabled me to write a story, which is just not about facts and figures, it is about two people.

AMT: It's emblematic of the hardship and the sort of the humanity buried in so much trauma.

HM: Yeah, absolutely. And it was that humanity that kept him going time after time.

AMT: What can we learn from hearing Lale Sokolova's story today?

HM: You know he used to say to me, humans, people are going to be the only ones that can save the day. Don't trust your governments he would say. Don't you trust politicians. They will not save you. It will be the man in the next street. You just try and do one thing he would say to me, just do one thing good every day if you can. And when I would see him, I'd often say ok Lale, what did you do today? And he'd say oh nothing much. I didn't go out today. He said, until later in the day and I realized I hadn't done anything. He said I'll take the doggies for a walk. Then I find a stranger and I smile at them and then I feel better.

AMT: How did hearing his story over time and then writing his story in a novel change you?

HM: Well I went through a period when it actually affected me quite severely. Thankfully that was short lived. And I need to tell you that in that book, you get about 10 per cent of what I know and what I've heard because no good can come from you hearing it all this well. And yes, I then had to come to that realization well, tell myself this is not your pain. This is not your trauma. You don't get to own it. So just back off and help where you can. Tell Lale's story. But what it did do was I learned about this time in history that I keep seeing continuing. All I can do now is talk to as many people as will want to hear Lale's story and feel so damn good about the fact that I get thousands of letters from people, who say that just hearing his story makes them want to lead their life differently.

AMT: And you know you have events in there. At one point, I think it's about a year before the the Russians started advancing. An allied plane flies over and you describe through the novel, people yelling bomb it. Bomb it. Like they want the allies to bomb the gas chambers or anything just to stop this right because they obviously, no one is coming to their aid and they're living through this hell. And of course, after the war, this remains a real controversy that neither the railways, nor the gas chambers were ever bombed. And clearly the planes were flying over and taking a look.

HM: Oh they were taking a look and they're also photographing. I've seen aerial photographs that are now available that showed what was going on there. The allies they knew, but from what I understand from the heads of Washington and London, to do anything to help them, would be diverting from the war effort. And they had a plan and that wasn't in their plan. So yes they did nothing.

AMT: It's a reminder of the of the personal suffering that goes on when so many people were so helpless.

HM: Yes, utterly. Utterly. And all they had was each other.

AMT: Well you introduced us to one man with an incredible story about many people. Thank you very much.

HM: You are very, very welcome.

AMT: That's Heather Morris, the author of the nove,l "The Tattooist of Auschwitz," based on the real life of Lale Sokolov, who tattooed numbers on the arms of fellow prisoners at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps. If you go to our website, we have pictures of Lale Sokolov and his wife, Gita, cbc.ca/thecurrent. Heather Morris spoke to me from Melbourne, Australia. I'm Anna Maria Tremonti. Thanks for listening to The Current.