It was the snow that woke the dog. He lifted his head. He sniffed.

Snow, yes. But there was another smell, the scent of something wild and large.

Iddo got to his feet. He stood at attention, his tail quivering.

He barked. And then he barked again louder.

“Shhh,” said Tomas.

But the dog would not be silenced.

Something incredible was approaching. He knew it, absolutely, to be true. Something wonderful was going to happen, and he would be the one to announce it. He barked and barked and barked.

He worked with the whole of his heart to deliver the message.

Iddo barked.

Upstairs, in the dorm room of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, Adele heard the dog barking. She got out of bed and walked to the window and looked out and saw the snow dancing and twirling and spinning in the light of the street lamp.

“Snow,” she said, “just like in the dream.” She leaned her elbows on the windowsill and looked out at the whitening world.

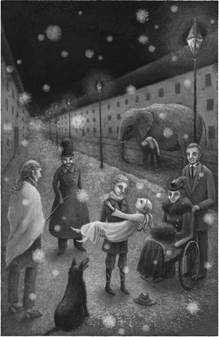

And then, through the curtain of falling snow, Adele saw the elephant. She was walking down the street. She was following a boy. There was a policeman and a man pushing a woman in a wheelchair and a small man who was bent sideways. And the beggar was there with them, and so was the black dog.

“Oh,” said Adele.

She did not doubt her eyes. She did not wonder if she was dreaming. She simply turned from the window and ran in her bare feet down the dark stairway and into the great room and from there into the hallway and past the sleeping Sister Marie. She threw wide the door to the orphanage.

“Here!” she shouted. “Here I am!”

The black dog came running toward her through the snow. He danced circles around her, barking, barking, barking.

It was as if he were saying, “Here you are at last. We have been waiting for you. And here, at last, you are.”

“Yes,” said Adele to the dog, “here I am.”

The draft from the open door woke Sister Marie.

“The door is unlocked!” she shouted. “The door is always and forever unlocked. You must simply knock.”

When she was fully awake, Sister Marie saw that the door was, in fact, wide open and that beyond the door, in the darkness, snow was falling. She got up from her chair and went to pull the door closed and saw that there was an elephant in the street.

“Preserve us,” said Sister Marie.

And then she saw Adele standing in the snow, in her nightgown and with no shoes on her feet.

“Adele!” Sister Marie shouted. “Adele!”

But it was not Adele who turned to look at her. It was a boy with a hat in his hands.

“Adele?” he said.

He spoke the name as if it were a question and an answer both, and his face was alight with wonder.

The whole of him, in fact, shone like one of the bright stars from Sister Marie’s dream.

He picked her up because it was snowing and it was cold and her feet were bare and because he had promised their mother long ago that he would always take care of her.

“Adele,” he said. “Adele.”

“Who are you?” she said.

“I am your brother.”

“My brother?”

“Yes.”

She smiled at him, a sweet smile of disbelief that turned suddenly to belief and then to joy. “My brother,” she said. “What is your name?”

“Peter.”

“Peter,” she said. And then again, “Peter. Peter. And you brought the elephant.”

“Yes,” said Peter. “I brought her. Or she brought me, but in any case, it is all the same and just as the fortuneteller said.” He laughed and turned. “Leo Matienne,” he shouted, “this is my sister!”

“I know,” said Leo Matienne. “I can see.”

“Who is it?” said Madam LaVaughn. “Who is she?”

“The boy’s sister,” said Hans Ickman.

“I don’t understand,” said Madam LaVaughn.

“It’s the impossible,” said Hans Ickman. “The impossible has happened again.”

Sister Marie walked out through the open door of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light and into the snowy street. She stood next to Leo Matienne.

“It is, after all, a wonderful thing to dream of an elephant,” she said to Leo, “and then to have the dream come true.”

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne, “yes, it must be.”

Bartok Whynn, who stood beside the nun and the policeman, opened his mouth to laugh and then found that he could not. “I must —” he said. “I must —” But he did not finish the sentence.

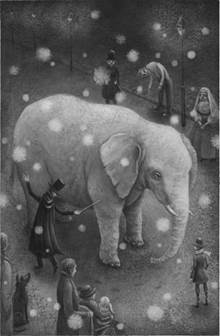

The elephant, meanwhile, stood in the falling snow and waited.

It was Adele who remembered her and said to her brother, “Surely the elephant must be cold. Where is she going? Where are you taking her?”

“Home,” said Peter. “We are taking her home.”

Peter walked in front of the elephant. He carried Adele. Next to Peter walked Leo Matienne. Behind the elephant was Madam LaVaughn in her wheelchair, pushed by Hans Ickman, who was, in turn, followed by Bartok Whynn, and behind him was the beggar, Tomas, with Iddo at his heels. At the very end was Sister Marie, who for the first time in fifty years was not at the door of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light.

Peter led them, and as he walked through the snowy streets, each lamppost, each doorway, each tree, each gate, each brick leaped out at him and spoke to him. All the things of the world were things of wonder that whispered to him the same thing. Each object spoke the words of the fortuneteller and the hope of his heart that had turned out, after all, to be true: she lives, she lives, she lives.

And she did live! Her breath was warm on his cheek.

She weighed nothing.

Peter could have happily carried her in his arms for all eternity.

The cathedral clock tolled midnight. A few minutes after the last note, the magician heard the great outer door of the prison open and then close again. The sound of footsteps echoed down the corridor. The steps were accompanied by the jangle of keys.

“Who comes now?” shouted the magician. “Announce yourself!”

There was no answer, only footsteps and the light from the lantern. And then the policeman came into view. He stood in front of the magician’s cell and held up the keys and said, “They await you outside.”

“Who?” said the magician. “Who awaits me?” His heart thumped in disbelief.

“Everyone,” said Leo Matienne.

“You succeeded? You brought the elephant here? And Madam LaVaughn as well?”

“Yes,” said the policeman.

“Merciful,” said the magician. “Oh, merciful. And now it must be undone. Now I must try to undo it.”

“Yes, now it all rests upon you,” said Leo. He inserted the key into the lock and turned it and pushed open the door to the magician’s cell.

“Come,” said Leo Matienne. “We are, all of us, waiting.”

There is as much magic in making things disappear as there is in making them appear. More, perhaps. The undoing is almost always more difficult than the doing.

The magician knew this full well, and so when he stepped outside into the cold and snowy night, free for the first time in months, he felt no joy. Instead, he was afraid. What if he tried and failed again?

And then he saw the elephant, the magnificence of her, the reality of her, standing there in the snow.

She was so improbable, so beautiful, so magical.

But no matter, it would have to be done. He would have to try.

“There,” said Madam LaVaughn to Adele, who was in the noblewoman’s lap, wrapped up tight and warm, “there he is. That is the magician.”

“He does not look like a bad man,” said Adele. “He looks sad.”

“Yes, well, I am crippled,” said Madam LaVaughn, “and that, I assure you, goes somewhat beyond sadness.”

“Madam,” said the magician. He turned away from the elephant and bowed to Madam LaVaughn.

“Yes?” she said to him.

“I intended lilies,” said the magician.

“Perhaps you do not understand,” said Madam LaVaughn.

“Please,” said Hans Ickman, “please, I beg you! Speak from your hearts.”

“I intended lilies,” continued the magician, “but in the clutches of a desperate desire to do something extraordinary, I called down a greater magic and inadvertently caused you a profound harm. I will now try to undo what I have done.”

“But will I walk again?” said Madam LaVaughn.

“I do not think so,” said the magician. “But I beg you to forgive me. I hope that you will forgive me.”

She looked at him.

“Truly, I did not intend to harm you,” he said. “That was never my intention.”

Madam LaVaughn sniffed. She looked away.

“Please,” said Peter, “the elephant. It is so cold, and she needs to go home, where it is warm. Can you not do your magic now?”

“Very well,” said the magician. He bowed again to Madam LaVaughn. He turned to the elephant. “You must, all of you, step away, step back. Step back.”

Peter put his hand on the elephant. He let it rest there for a moment. “I’m sorry,” he said to her. “And I thank you for what you did. Thank you and good-bye.” And then he stepped away from her, too.

The magician walked, circling the elephant and muttering to himself. He thought about the star on view from his prison cell. He thought about the snow falling at last, and how what he had wanted more than anything was to show it to someone. He thought about Madam LaVaughn’s face looking up into his, questioning, hoping.

And then he began to speak the words of the spell. He said the words backward, and he said the spell backward, too. He said it, all of it, under his breath, with the profound hope that it would well and truly work, and with the knowledge, too, that there was only so much, after all, that could be undone, even by magicians.

He spoke the words.

The snow stopped.

The sky became suddenly, miraculously clear, and for a moment the stars, too many of them to count, shone bright. The planet Venus sat among them, glowing solemnly.

It was Sister Marie who noticed. “Look there,” she said. “Look up.” She pointed at the sky. They all looked: Bartok Whynn, Tomas, Hans Ickman, Madam LaVaughn, Leo Matienne, Adele.

Even Iddo raised his head.

Only Peter kept his eyes on the elephant and the magician who was walking around and around her, muttering the backward words of a backward spell that would send her home.

And so Peter was the only one to see her leave. He was the only one to witness the greatest magic trick that the magician ever performed.

The elephant was there, and then she was not.

It was as simple as that.

As soon as she was gone, the clouds returned, the stars disappeared from view, and it began, again, to snow.

It is incredible that the elephant, who had arrived in the city of Baltese with so much noise, left it in such a profound silence. When she at last disappeared, there was no noise at all, only the tic-tic-tic of the falling snow.

Iddo put his nose up in the air and sniffed. He let out a low, questioning bark.

“Yes,” Tomas said to him, “gone.”

“Ah, well,” said Leo Matienne.

Peter bent over and looked at the four circular footprints left in the snow. “She is truly gone,” he said. “I hope she is home.”

When he raised his head, Adele was looking at him, her eyes round and astonished.

He smiled at her. “Home,” he said.

And she smiled back at him, that same smile: disbelief, then belief, and finally joy.

The magician sank to his knees and put his head in his shaking hands. “I am done with it then, all of it. And I am sorry. Truly, I am.”

Leo Matienne took hold of the magician’s arm and pulled him to his feet.

“Are you going to put him back in prison?” said Adele.

“I must,” said Leo Matienne.

And then Madam LaVaughn spoke. She said, “No, no. It is pointless, after all, is it not?”

“What?” said Hans Ickman. “What did you say?”

“I said that it is pointless to return him to prison. What has happened has happened. I release him. I will press no charges. I will sign any and all statements to that effect. Let him go. Let him go.”

Leo Matienne let go of the magician’s arm, and the magician turned to Madam LaVaughn and bowed. “Madam,” he said.

“Sir,” she said back.

They let him walk away.

They watched his black coat retreating slowly into the swirling snow. They watched, together, until it disappeared entirely from view.

And when he was gone, Madam LaVaughn felt some great weight suddenly flap its wings and break free of her. She laughed aloud. She put her arms around Adele and hugged her tight.

“The child is cold,” she said. “We must go inside.”

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne. “Let’s go inside.”

And that, after all, is how it ended.

Quietly.

In a world muffled by the gentle, forgiving hand of snow.

Iddo slept in front of the fire when he came to visit.

And Tomas sang.

They did not ever, the two of them, stay for long.

But they visited often enough that Leo and Gloria and Peter and Adele learned to sing, along with Tomas, his strange and beautiful songs of elephants and truth and wonderful news.

Often, when they were singing, there came from the attic apartment a knocking sound.

It was usually Adele who went up the stairs to ask Vilna Lutz what it was he wanted. He could never answer her properly. He could only say that he was cold and that he would like for the window to be closed; sometimes, when he was in the grips of a particularly high fever, he would allow Adele to sit beside him and hold his hand.

“We must outflank the enemy!” he would shout. “Where, oh where, is my foot?”

And then, in despair, he would say, “I cannot take her. Truly, I cannot. She is too small.”

“Shhh,” said Adele. “There, there.”

She would wait until the old soldier fell asleep, and then she would go back down the stairs to where Gloria and Leo and her brother were waiting for her.

And when she walked into the room, it was always, for Peter, as if she had been gone a very long time. His heart leaped up high inside of him, astonished and overjoyed anew at the sight of her, and he remembered, again, the door from his dream and the golden field of wheat. All that light, and here was Adele before him: warm and safe and loved.

It was, after all, as he had once promised his mother it would be.

The magician became a goatherd and married a woman who had no teeth. She loved him, and he loved her, and they lived with their goats in a hut at the foot of a steep hill. Sometimes, on summer evenings, they climbed the hill and stood together and stared up at the constellations in the night sky.

The magician showed his wife the star that he had gazed upon so often in prison, the star that, he felt, had kept him alive.

“It is that one,” he said, pointing. “No, it is that one.”

“It makes no never mind which it was, Frederick,” his wife said gently. “All of them are beautiful.”

And they were.

The magician never again performed an act of magic.

The elephant lived a very long time. And in spite of what they say about the memory of elephants, she recalled none of what had happened. She did not remember the opera house or the magician or the countess or Bartok Whynn. She did not remember the snow that fell so mysteriously from the sky. Perhaps it was too painful for her to remember. Or maybe the whole of it seemed to her like nothing more than a terrible dream that was best forgotten.

Sometimes, though, when she was walking through the tall grass or standing in the shade of the trees, Peter’s face would flash in front of her, and she was struck with a peculiar feeling of having been well and truly seen, of having at last been found, saved.

And then the elephant was grateful, although she did not know to whom and could not think why.

And as the elephant forgot the city of Baltese and its inhabitants, so they, too, forgot her. Her disappearance caused a stir and then was forgotten. She became to them a strange and unbelievable notion that faded with time. Soon, no one spoke of her miraculous appearance or her inexplicable disappearance; all of it seemed too impossible to have ever happened to begin with, to have ever been true.

But it did happen.

And some small evidence of these marvelous events remains.

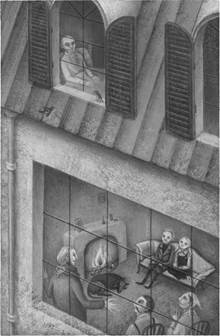

High atop the city’s most magnificent cathedral, hidden among the glowering and resentful gargoyles, there is a carving of an elephant being led by a boy. The boy is carrying a girl, and one of his hands is resting on the elephant, while behind the elephant, there is a magician and a policeman, a nun and a noblewoman, a manservant, a beggar, a dog, and finally, behind them all, at the end, a small bent man.

Each person has a hold of the other, each one is connected to the one before him, and each of them is looking forward, their heads held at such an angle that it seems as if they are looking into a bright light.

If you yourself ever journey to the city of Baltese, and if, once you are there, you question enough people, you will — I know; I do believe — find someone who can lead you, someone able to show you the way to that cathedral, to that truth that Bartok Whynn left carved there, high up in the stone.