GRACE’S STORY

It was a “time of fire” as Grace called it, when she and Dumi had marched in the streets with thousands of other schoolchildren. They were protesting that their schools taught them only what the white government wanted them to know.

On the banner that Dumi and his friends carried, they had written ‘BLACKS ARE NOT DUSTBINS.’

Everything went all right until the police saw the schoolchildren marching, and then the trouble started. The police aimed their guns and began to shoot with real bullets, killing whoever was in the way.

It was terrible. The police shot tear gas too, making everyone’s eyes burn.

People were screaming, bleeding, falling. More police came in great steel tanks, and more in helicopters, firing from above. A little girl standing near Grace, about eight years old, raised her fist, and next thing she was lying dead.

People became fighting mad, throwing stones at the police, burning down schools and government offices. Smoke and flames were everywhere.

But the police kept shooting, until hundreds were dead. Hundreds were hurt and hundreds were arrested.

Dumi was one of those arrested.

When he came out of prison, he said that the police had beaten him up badly, but he would go on fighting even if they killed him.

Then one night he disappeared. When their mother went to each police station, asking if he was there, the police said “No”. But maybe they were lying. Maybe they had killed him too.

For a year they had no news.

Until one day a letter came. It was from Dumi. There was no address, but it had been posted in Johannesburg. Dumi wrote that he was well and studying in another country. He was giving the letter to a friend to post. He also wrote that he would be coming back one day. Coming back to help fight for FREEDOM and make life better for everyone. He had written FREEDOM in big letters.

The family had been so excited that he was alive, so worried about the dangers he faced, yet so proud of his courage. Dumi had been a boy when he left, but now he would be a man. Although it was a long time since they had heard from him, they hadn’t given up hope. They were still waiting.

When Grace finished talking, the children remained quite silent.

“Well, it’s time to sleep,” Grace said, pushing back her chair and stretching herself up. Her young brothers cleared up the dishes, stacking them up ready to wash them outside in the morning.

Grace shared her bed with Naledi and the boys shared theirs with Tiro. He was soon fast asleep but Naledi lay awake for a while, thinking.

So much had happened. She wondered what her mother was doing. Was Mma alone in the little room in the yard, or was she still watching over the child in the big house?

Naledi was sure Mma must be thinking of Dineo. Why couldn’t Mma have left straight away, and what if something happened to Dineo before they arrived? Naledi didn’t want to think about that. At least the delay had led to them being with Grace, and she really liked Grace.

Her mind wandered over the terrible events in Soweto, to Dumi and to the word in big letters – FREEDOM. What did the word really mean? Did it mean they could live with their mother? Did it mean they could go to secondary school? But Grace said the children marched because they had to learn a lot of “rubbish” in school. So what would you learn in a school with FREEDOM?

There were so many questions, Naledi thought, as she drifted into sleep.

JOURNEY HOME

“Wake up! It’s five o’clock.”

When Grace’s voice reached Naledi and Tiro, they pulled themselves up. Silently they drank the tea Grace had made before slipping quietly out of the house, leaving Jonas and Paul still asleep.

It was half dark, but already many people were hurrying towards the station, and the train was crowded all over again. Most of the faces still looked tired. Bones squeezed against bones as they jolted, jerked and swayed with each movement of the train. At each station yet more bodies crammed in against them, until at last they were thrown out with the crowd rushing off to another day’s work in Johannesburg.

When they arrived at the main ticket office, Mma was already waiting with her case. She thanked Grace warmly.

“Any time you need help, let me know,” Mma added.

“Tsamaya sentle,” Grace called as they parted at the barrier.

“Sala sentle!” They waved goodbye as they went.

The train going home wasn’t crowded so the children sat by the window, hoping to see places they had passed on the way, especially the orange farm where they had spent the night. They told Mma about the boy who had helped them. She said quietly, “That was brave of him. He could have got into a lot of trouble.”

“Mma, do you know Grace has a br—”

Tiro was beginning to talk about Dumi, but Naledi quickly nudged him with her foot and gave him a stern look. The scatterbrain! Already he was forgetting the promise they had made to Grace. Tiro bit his lip, but fortunately Mma hadn’t noticed anything.

“Those children should be in school,” Mma continued, still thinking about the boy on the farm.

Naledi lay with her head against her mother’s shoulder. It was so confusing. Here was Mma saying that children should be in school, and there was Grace saying that schools taught black children rubbish.

Didn’t Dumi and his friends carry a poster saying ‘BLACKS ARE NOT DUSTBINS!’

What did Mma think about that and all the shooting? Had she heard about the little girl who was killed close to Grace? Mma had never spoken to them about such things. Did she think they were too young to be told?

Naledi stared out of the window, without seeing anything. Her mind was too full of questions. Surely she could talk to Mma about what was troubling her? As she leant against Mma’s body and felt its warmth, it seemed silly to hold back problems. Especially when their time together was so short.

“Mma …” Naledi began, turning to look up at her mother’s face. “Grace told us how the schoolchildren marched in the streets …”

Naledi stopped, seeing shock and pain flash through Mma’s eyes. She became even more alarmed when Mma remained quite silent for what seemed like an age, gazing down at her lap.

At last, Mma spoke very softly. “Do you know how many children died on those streets? Do you know how many mothers were crying ‘Where’s my child’?”

Mma was shaking her head slowly. There was another long pause, as if she was thinking whether to say any more. Then she leant forwards and covered her face with one hand, wiping her forehead.

“You know, every day I must struggle … struggle … to make everything just how the Madam wants it. The cooking, the cleaning, the washing, the ironing. From seven every morning, sometimes till ten, even eleven at night, when they have their parties. The only time I sit is when I eat! But I keep quiet and do everything, because if I lose my job I won’t get another one. This Madam will say I am no good. Then there will be no food for you, no clothes for you, no school for you.”

Mma pulled her back up straight and put an arm around her children. Tiro shifted to come closer.

“It’s very bad, Mma,” Naledi said, in a low voice.

“Yes, it’s bad. But those children who marched in the streets don’t want to be like us … learning in school just how to be servants. They want to change what is wrong … even if they must die!”

“Oh, Mma, oh, Mma,” Naledi whispered.

Tiro clutched Mma’s hand and she pulled him towards her lap.

“What did their parents say?” he asked.

“Some tried to stop their children so they wouldn’t get hurt, but there were also parents who helped them.”

Mma explained how the children had asked their parents not to work on certain days, and how many people had stayed at home. It had been a time of terrible worry for Mma’s friends who had families in Soweto. The eldest Mbatha boy had been arrested and Mma told them about his mother’s dreadful search at all the police stations.

So … Mma knew something about Dumi, Naledi thought. But neither she nor Tiro broke their own promise.

When Mma finished speaking, they sat in silence. They watched the train stop at stations on the way, passengers climbing in and out with cases, bags and bundles.

Vast stretches of land flashed by; grassland, mountains, grassland again. Naledi suddenly felt very small. Before this journey to fetch Mma, she had never imagined that all this land existed. Nor had she any idea of what the city was like. She had never known a person like Grace before, and she had never known her own mother in the way she was beginning to know her now …

“That’s it. I’m sure that’s it!”

Tiro’s voice startled Naledi from her thoughts, but already the orange farm to which he was pointing was in the distance. Mma nodded with a slight smile.

THE HOSPITAL

None of them spoke after that, their thoughts all turned to Dineo. When the train pulled in at their station, Mma hurried the children out on to the platform. Outside, she spoke anxiously to a man standing against a car. After she had taken some notes from her purse, he agreed to take them first to their village and then go on to the hospital. So much money, thought Naledi. Mma must have borrowed it.

As the car bumped along the road into the village, churning up the dust, it seemed longer than two days that they had set off walking. Mma directed the driver to the house and people looked up as the car passed by. It wasn’t often a car came this way. The sound of the engine brought Nono and Mmangwane outside. Nono looked so thin and weary, but her eyes lit up when she saw whom it was.

“The child is very sick,” she whispered in a low voice.

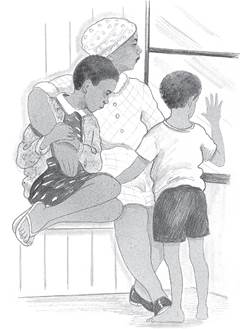

Mma rushed in and came out clasping Dineo close to her, the little girl lying limply in Mma’s arms, her eyes sunken.

“You children must stay with Nono,” Mma said firmly, as they struggled to bring the case out of the car.

“Oh please, Mma, can’t I come with you? Please?” Naledi pleaded. “Tiro can help Nono.”

Mma looked across at Nono, whose tired face nodded “yes”. Naledi gave her grandmother a quick hug.

“Thank you, Nono! Tiro will tell you everything … and please don’t be angry with us. We’re very sorry we gave you more worry.”

“But we had to get Mma!” put in Tiro.

“Well, come in and tell us about it,” invited Mmangwane.

Nono put an arm round Tiro’s shoulders as they waved goodbye. From inside the car Naledi watched the little group grow smaller until they had quite disappeared behind the clouds of dust.

As the car now jerked its way back to the town over the rough roads, Mma cradled Dineo in her arms, whispering soft words to her. Naledi held Dineo’s little hand, stroking and playing gently with her fingers. But the little girl made no response. Each minute on the way to the hospital now seemed important. What if they got there just a minute too late. That couldn’t happen … could it?

At last they were travelling through the town, and then out into the open again, until at last there was a cluster of low white buildings with a few trees and bushes scattered between them. Some people were waiting by the roadside outside the hospital, and as soon as Mma and Naledi climbed out of the car, an old man came hobbling over to the driver. He was followed by others and almost immediately the car, packed tight with people, was rumbling off back to the town.

Naledi stayed close to Mma as she made her way past people sitting or lying down on the ground in front of the buildings. A lady with a thin blanket wrapped over her shoulders pointed the way.

Around the corner they found the queue of patients. It led up to a verandah where a woman in white sat at a desk.

“Is that the doctor for Dineo?” Naledi whispered.

Mma shook her head. “No. We must get a card first. The doctor is inside.”

The queue moved very slowly as people shuffled forwards after every few minutes. Some patients, who were too weak to stand, lay wedged against the wall and had to be helped along. Just in front of Mma and Naledi was a young woman with a small baby tied in a blanket to her back. Naledi wondered if the woman or the baby was the patient.

The sun shone down on the queue. Mma tried to screen Dineo from the glare, but the heat seemed to soak in everywhere and Dineo began to whimper. Mma tried rocking her gently, while Naledi tried singing her little songs which had always made her laugh. However, now Dineo didn’t even seem to hear them …

When finally it was Mma’s turn at the desk, Naledi relaxed a little. Now Dineo could go inside and be given medicine. But when Mma led the way down a corridor and into a room filled with far more people than had been outside, Naledi felt panic grip her.

“Are all these people before Dineo, Mma?” she cried softly.

“They are also very sick, Naledi. We must be patient.”

They were lucky to find space on a bench next to the young woman with the baby. She didn’t look much older than Grace, thought Naledi.

It was the young woman who spoke first.

“It’s always long to wait. I was here before with my baby and now he’s sick again.”

“What’s the problem?” Mma asked.

“Last time the doctor said he must have more milk, but I’ve no money to buy it.”

Mma sighed. “I think it’s the same sickness with my child.”